A Tale of Two Sisters

In 2018, London art dealer Philip Mould acquired a rather unusual portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Though naive in its composition, the painting was immediately compared to a series of early portraits showing an image of the young Queen Elizabeth, known as the ‘Clopton Type’.

I have discussed the ‘Clopton Type’, and its possible evolution in a previous article on The Philip Portrait, so I will not go into detail regarding this in this article. The Butler portrait, as I will call it in this study, does appear to reinforce my opinion that the ‘Clopton Type’ was derived from an earlier portrait known as the Berry-Hill portrait. During my research, I have also managed to locate a possible ‘sister portrait’ and some provenance information regarding the Butler portrait. As this painting is an important artifact in terms of the iconography relating to Queen Elizabeth I, I will use this article to document the discoveries.

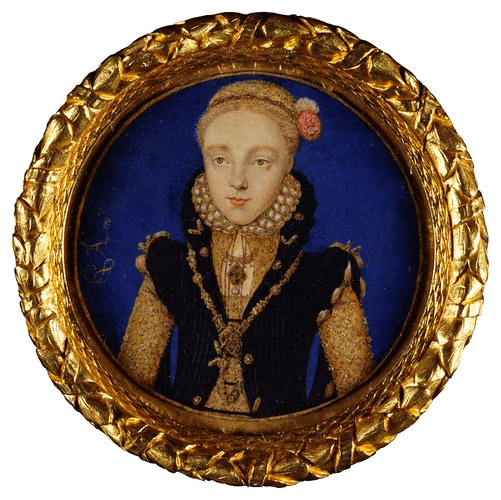

Queen Elizabeth I

Oil on Panel

© Philip Mould Gallery, London

Constructed with the use of three vertical oak panels, measuring 95.5cm x 65cm in diameter. Elizabeth is seen standing three-quarter length, full frontal, with her head turned, slightly, towards the viewers left. The young Queen is missing her trademark wig of long red curls, her hair is simply parted in the middle, pulled back, and worn under a coif and black hood. At her neck she wears a large ruff that surrounds her face, she also wears a lose gown of damask cloth of gold, and a black velvet surcoat, with a large fur collar and hanging sleeves. In her hand, she holds a book, and three rings are visible on her fingers. The portrait is entirely different to the images of power, wealth and majesty that has become illustrious with one of England’s most famous monarchs.

Mould purchased the portrait when it was sold by Tennants Auctioneers on 18th November 2017. Described in the catalogue for the sale as ‘English School, follower of Hans Eworth, portrait of a young lady, reputed to be Queen Elizabeth I’, the confirmed connection to Elizabeth had not been established at this point. The auction house did note some similarities to the ‘Clopton Type’, however, also noted some ‘notable differences, including handling of brushwork, the portrait length, positioning of the hands, costume variances and the omission of the large jewel worn on a double chain known as the Mirror of France’. Almost nothing was provided regarding the provenance of the painting, other than it had come from a private English collection and had been purchased by the then owner from Oakham Fine Art in 1996.[1]

Mould immediately sent the portrait to be cleaned, restored and dendrochronology tested, to establish a date of creation. The right-hand side panel had come adrift from the other two and this was once again secured. Discoloured varnish and overpaint was removed and a date of ’circa 1559’ was established for the portrait’s creation. Mould immediately noted that the Butler portrait was indeed related to the ‘Clopton Type’ and was, in fact, an earlier example. He concluded that the portrait was painted early in her reign, before Elizabeth, herself, truly understood the power of art, and noted that it was possibly one of the portraits Elizabeth attempted to eliminate with the draft proclamation of 1563. Mould would later put the Butler portrait on public display in his gallery, identifying the huge significance of the portrait being one of the earliest representations of Elizabeth as Queen of England in related news stories.[2]

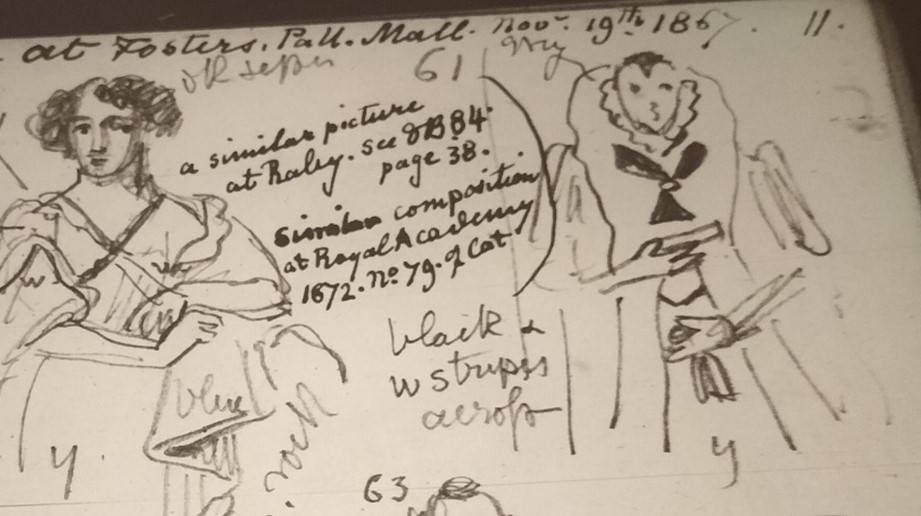

When looking for the possible provenance of this painting, I initially returned to the sketchbooks of Sir George Scharf in the Heinz archive, London. A valuable resource for anyone interested in art history, the gallery holds a total of two-hundred and twenty-three sketchbooks in its collection today. These are separated into two categories, the first being the sketchbooks created in a personal capacity and second being Trustee sketchbooks, created to document possible acquisitions for the Galleries collection. Due to their significance and fragility, the originals documents are closely guarded; however, in 1978, the archive opted to put the entire collection on microfilm, and it is this that the public view when requesting to see the sketchbooks.[3]

Unfortunately, the index system for the sketchbooks can be a little confusing, and in some cases, I have found it is best to just jump straight in and see what can be found. In the case of the Butler portrait this was successful, and it appears from one of the Trustee sketchbooks that Scharf, himself, viewed the portrait or a similar copy in 1867. Scharf made a rough sketch of the painting, however, provided little information other than it was seen at ‘Foster’s, Pall Mall. 19th November 1867’. [4]

NPG100/1/1

© Heniz Archive, London

Edward Foster’s, or Foster and Son as it was better known was an auction house in London, which was established in 1833. Unfortunately, to date, I have been unable to locate the auction catalogue for the sale mentioned by Scharf, however, this has been added to my list and attempts will be made to locate this on my next trip to London.

The portrait appears again when an image was published in The Illustrated London News in 1938. The photograph seen, shows the painting prior to some of the restoration work removed by Philip Mould, and the article notes that the portrait was in the collection of Ewart Park in Northumberland.[5] The identification of the sitter, at that time, was incorrectly thought to be ‘Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland’ and the portrait was also incorrectly dated to the fifteenth century. Size and materials used was also listed among the information provided.[6]

© British Library Newspaper Archive

Built in the eighteenth century, and home to the St. Pauls and Butler family, the portrait and property was inherited by Horace Butler on the death of his father George Grey Butler in 1935. George Grey Butler had begun selling some of the family’s possessions off in the 1920’s due to financial issues. [7] On his father’s death, Horace Butler was unable to maintain the cost of the upkeep for Ewart Park, it was briefly occupied by the military during World War II and was eventually sold by the family. At present, no auction catalogue has been located for the contents of Ewart park, it may be possible that what little was left in the property, the family opted to take with them and was sold at a later date.

Sadly, for now, the provenance trail stops with Ewart Park, however, I do have one final interesting piece of information to share, connected to the Butler portrait. Stored within the Icon Notes relating to Mary Tudor in the Heinz Archive London, is a rather interesting collection of letters and photographic images concerning a portrait of Queen Mary, and it could be argued that both portraits of the two sisters are related.[8]

Unknown Artist, previously attributed to Clouet.

© Heinz Archive, London

Dated to the early 1980’s, and from a private collector in France, the letters reports that she had inherited her portrait from her sister, who had purchased the painting in the in the 1950’s from Tours in France. She also notes that the portrait has a label on the back stating that it was transferred from panel to canvas, and the artist associated with its creation was French artist Francois Clouet.

What can clearly be seen from the image above is that both portraits show the same characteristic approach when it comes to composition, style, and approach. Unfortunately, the portrait of Queen Mary is currently missing, and it is hard to establish form the photograph if some later restoration work and overpaint has taken place.

As we have identified in many of the articles concerning the B Pattern of Anne Boleyn, the creation of portrait sets within the sixteenth century, stems a lot further back than initially thought. Portrait sets were often unified using a curtain, pillow, or background colour. As both portraits of Elizabeth and Mary include the unique pattern work seen on the gold demask fabric of the gowns, it may just be possible that both were part of an early set of portraits displaying the Tudor monarch. Unfortunately, until the portrait of Queen Mary is located and tested to establish possible overpaint and date of creation, we may not know for sure. The incorporation of the pattern in both portraits cannot be put down to coincidence and some further research will need to take place to identify any possible connection between both paintings.

[1] Tennants Auction Catalogue, Autum Sale, 18th November 2017, lot 66

[2] Moufarrige. Natasha, earliest full-length portrait of Queen Elizabeth I revealed – Showing her as studious and shy young woman, Daily Telegraph, June 17th 2018.

[3] National Portrait Gallery. The Notebooks of Sir George Scharf (1820-95), World Microfilm Publications, 1978, P.1

[4] Heinz Archive. NPG100/1/1, Sketchbook of George Scharf (1886-1888), P. 11

[5] Clarification is currently needed to identify if the black ribbon and ring seen around the sitter’s neck and the object seen in the sitter’s right hand is original to the painting or later overpaint. Both items can clearly still be seen in the portrait today after restoration work had taken place, however, it may possibly have been deemed not to take the portrait back to its original state and the overpaint was simply left in place. interestingly, the same black ribbon and ring can be seen in the ‘La Royne D’Angleterre’ drawing of Elizabet discussed in my article on the Paine Miniature. See https://ladyjanegreyrevisited.com/2021/05/12/the-paine-miniature-is-it-elizabeth/ for more information

[6] Illustrated London news, Personalities of The Tudor and Stuart Period, 29th October 1938 p.30

[7] I have been able to locate eight Sotheby and Co auction catalogues from the years on 1928-29 that all include property from the estate of Mr George Grey Butler of Ewart Park, Northumberland

[8] Heinz Archive, London. NPG49/1/11, Notes on Sitters: Mary I, Queen of England. 1515-1558