Anne Boleyn

Oil on Panel

22 ¼ x 17 3/8 inches

© National Portrait Gallery, London

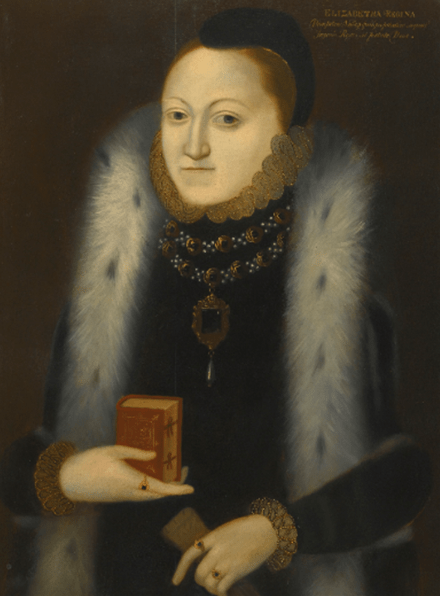

NPG 668 is not the only portrait of Anne Boleyn owned by The National Portrait Gallery, London. In 1974, the gallery purchased a set of sixteen portrait’s depicting Kings and Queens of England which also included a portrait of Anne. Though inferior in technique, and artistic quality to that of the now infamous NPG 668, the Hornby portrait or NPG 4980 (15) as it is better known was undoubtably created with the use of the B Pattern.

Executed with the use of oil on panel. The panel support is constructed with the use of two oak boards, seven millimetres thick, and aligned vertically to create one panel measuring 22 ¼ x 17 3/8 inches. The portrait depicts the head and upper torso of an adult female, placed before a plain background with her head turned slightly towards the viewers left. Her face is long, oval in shape, with a high forehead. Her hair is straight in texture, parted in the centre, and pulled back over her ears, and placed under her coif of gold fabric. Her eyes are brown, heavy lidded, and are crooked in appearance. She has full pink lips, an aquiline nose, and her eyebrows are pronounced with a strong shape. Anne is seen wearing her trademark French Hood, constructed of black fabric, ending just below the jawline, and the black veil is visible hanging down at the back. An upper billament of thirty-nine white pearls is visible on the back of the hood, and a lower billament of thirty-one pearls is seen at the front of the hood. At her neck she wears two strings of pearls with a large letter B pendant of goldsmith work with three hanging pearls suspended from the upper string. A chain constructed of loops of square goldsmith work is also seen at the neckline. Anne wears a French Gown constructed with the use of black fabric, cut square at the neck, and a white chemise, embroidered with blackwork. Sixteen square cut ouches, each containing a diamond, are attached to the neckline of her kirtle. A further sixteen ouches, constructed of goldsmith work, and five pearls, are also seen in between these. The turned back sleeves of the French Gown are constructed of a brown fabric, rather than the fur sleeves seen in other depictions.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

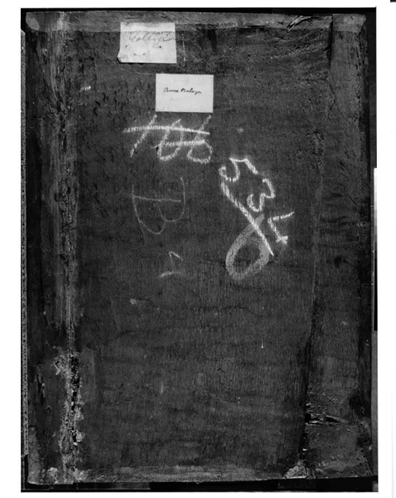

An inscription applied to the top of the panel in a yellow pigment identifies the sitter as ANNA. BOLLINA. VXOR. HENRICI. OCTAV or Anna Bollina wife of Henry Emperor. A handwritten label detailing The National Portrait Gallery registration number has also been applied to the back of the panel. No other inscriptions or labels are visible on the panel surface; however, it must be noted that the reverse of the panel was covered in a layer of balsa wood during early conservation treatment. I have been unable to obtain an image of the reverse of the panel prior to this treatment and I am unable to determine if any labels or further inscriptions lie below this.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

When purchased by The National Portrait Gallery in 1974, the paintings had come from the collection of George Osborne, 10th Duke of Leeds. It was recorded that the set had been on display at Hornby Castle, near Bedale. George Osborne died in 1927, and on his death his estate was broken up and eventually sold off. The portrait set had initially been stored by the National Portrait Gallery in the 1930’s and was later offered for purchase by the 10th Duke of Leeds Trust.[1]

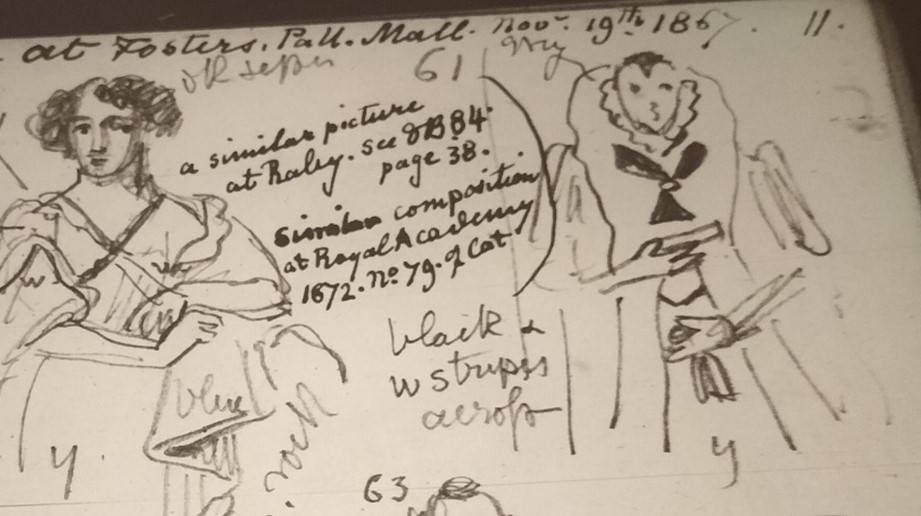

As with many of the portraits of Anne Boleyn seen in this study, documented information concerning them is scarce. In the case of the Hornby Portrait Set, we only start to see it appear in written documents towards the end of the nineteenth century. The first reference appears in 1868, when the collection of portraits was recorded as hanging in two rows in the Nursery Passage at Hornby Castle.[2]

Hornby Castle was originally built by the St. Quentin’s family in the fourteenth century and passed to the Conyers and Darcy families during the sixteenth century. By 1778, the property then passed into the possession of Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds, through his marriage to Amelia Darcy.[3]

Due to lack of documentation, it is not exactly known if the set had originated in the Leeds collection and was transferred to Hornby castle from another property. Or, if it had originated with the sixteenth century owners of Hornby Castle and was commissioned for that specific residence.

When purchased by The National Portrait Gallery, a full condition report was undertaken on each of the sixteen portraits included in the Hornby Set. The condition reports held in the registered packet for the portrait of Anne Boleyn identifies that at the time of purchase the left-hand side panel of NPG 4980(15) was in a weak condition due to a splitting of the joint, flaking paint layers and paint loss was also noted to the sitter’s neck and chin, and extensive oil retouching was also observed throughout the portrait. A thick layer of discoloured varnish was also viable on the panel surface.

Before Conservation Work

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Conservation work was commenced immediately on the portrait, to stabilise the panel, secure the joint, and apply a thin layer of balsa wood to the reverse of the portrait. The flaking paint layers were secured with the use of wax resin, and adhesive, and the later overpaint and discoloured varnish was also removed from the panel surface. A gesso filling was applied to the large areas of paint loss, and retouching was completed. The portrait was then revarnished with a conservation varnish.[4]

Though not scientifically analysed until 2011, In 1975, Robin Gibson suggested that the Hornby set was created over a long period of time. He also suggested that the set was made up and purchased as two or three smaller portrait sets, much like that seen with the Dulwich Set. Gibson separated the paintings into three distinctive groups in terms of date of creation, distinct differences in quality, and composition.

Group A: William I, Henry I, Stephan, Henry II, John, Edward II, was identified as being the later addition to the set, with Gibson estimating a date for creation as circa 1620-30.

Group B: Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Edward IV, Edward V, Anne Boleyn. Gibson identified that Dr John Fletcher of Oxford University had completed Dendrochronology testing on the portrait of Anne Boleyn and Richard III, and a date of 1590-1605 was established as the most likely period in with both portraits were painted.

Gibson identified Group B and Group C: Richard III, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Mary I, as a standard long gallery portrait set for this period. However, he also noted that Group C: contained a different characterisation in background and a higher quality craftmanship than that seen in the works of group B. Robin suggested that although group B and C were created at the same time, group C was probably purchased from alternative workshops, and it was Gibson’s dates and theory that was applied by the National Portrait Gallery to the set.[5]

In 2011, the Hornby portrait set finally underwent significant testing as part of the Making Art in Tudor Britian project at the National Portrait Gallery. During this, all portraits were dendrochronology tested, and it was identified that all panels were made from trees felled in the Eastern Baltic, between the 1580’s and early 1590’s.[6] Test also carried out on the paintings identified that the portraits were produced by several artists, using different painting techniques, and working across multiple workshops. [7] This suggested that the set was either produced as a single commission, and not added to over the course of time as suggested by Gibson or was assembled at the same time using ready- made paintings from different sellers.

As seen in my article on the Dulwich Portrait set, printed material published at a similar time to the Hornby sets creation also appears to be the source material used by some of the artist when creating the portraits for the Hornby Set. The portraits of William I, Henry I, Stephan, John, and Henry III show visual similarities to the full sheet woodcuts produced by an unknown artist and published in a book entitled ‘A Booke, containing the true portraiture of the countenances and attires of the kings of England’.

First published in London in 1597, by John de Beauchesne, this book pre-dates ‘Bazliologia’, the book thought to have been the source for the Dulwich set, by twenty-one years. Its author, who was only named as ‘T.T.’ is now thought to be Thomas Talbot, who also produced what is now called the Talbot Rose containing similar images of the English monarchs some eighth years earlier in 1589.

Though the importance of accurate historical documentation was still in its infancy towards the end of the sixteenth century, some of the illustration produced for Talbot’s book can today be matched with contemporary source materials depicting the sitter illustrated, which does suggest that the artist who created the illustration at least attempted to reproduce what was thought to be an authentic likeness.

When looking for a possible source for the portrait of Henry I, it could be argued that the image seen in the Hornby set shows a strong resemblance to the fifteenth century statue depicting the King at York Minster. Both the statue and painted image show similarities in the hair, the treatment of the beard, moustache, and the collar of the gown.

The portrait King Stephan also shows similarities to several contemporary illustrations showing the king with a bobbed hairstyle and beardless. Stephan is also seen beardless in his profile image on a silver penny from 1136 and is depicted in a full-frontal pose in the illustrated image for Matthew Paris’s ’Historia Anglarum’ produced between 1250 and 1259. Unfortunately, Talbot’s book does not include an image of Anne Boleyn, and it appears that artist who created the Hornby portrait looked elsewhere when depicting this legendary queen.

Sadley, NPG 4980(15) provides little information regarding the evolution of the B-pattern. The portrait is, however, it is one of a small number of paintings created with the use of this pattern that currently has a scientific date attached to it. What we can establish is that both NPG 4980(15) and NPG 668 were produced around the same time, and that both images were seen as, and identified as, an image of Anne by contemporary viewers towards the end of her daughter’s reign. This image would continue to be seen as a depiction of Anne Boleyn some thirty years later when Edward Alleyn purchased his portrait of Anne for the Dulwich set and continues to be reproduced as an image of Anne Boleyn to this day.

[1] Heniz Archive, National Portrait Gallery, Registered Packet NPG 4980(15)

[2] Catalogue of the Paintings and Portraits at Hornby Castle the Seat of the Duke of Leeds, 1868. The portrait set of Kings and Queens of England also appeared in subsequent catalogues detailing the collection at Hornby Castle, published in 1898 and 1902, and are again described as hanging in the ‘Nursery Passage’.

[3] Anon, Hornby Castle, Yorkshire, The Seat of the Duke of Leeds, Country Life Magazine, 1906, P 54-64

[4] Heniz Archive, National Portrait Gallery, Registered Packet NPG 4980(15), Technical Examination Report 1974

[5] Gibson Robin. The National Portrait Gallery’s set of Kings and Queens at Montacute House, National Trust Yearbook, 1975, P81-87

[6] Tyers. Ian, Tree-ring Analysis of Panel Paintings at the NPG, Group 4.5. March 2011, Registered Packet NPG 4980(15)

[7] Picturing History: A portrait set of early English kings and queens – National Portrait Gallery (npg.org.uk), accessed October 2023