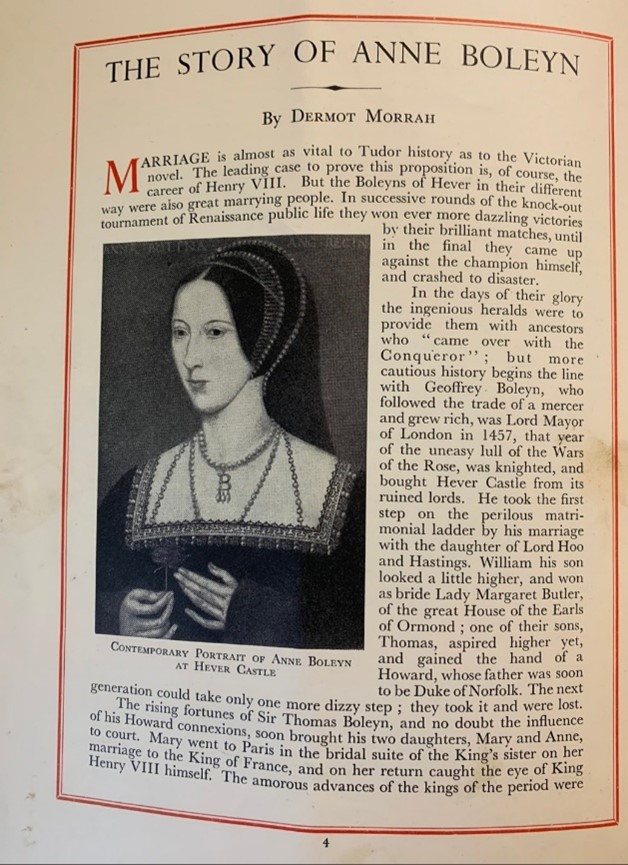

Stored within the large collection of paintings at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, and currently on long-term loan to Strawberry Hill House, is a rather unique collection of portraits depicting seventeen Kings and Queens of England. Today, the Dulwich Portrait set is one of the largest sets of portraits, depicting English Monarchs to survive. However, it has received little attention when it comes to the literature concerning the production of portraits sets during the latter part of the sixteenth and early seventeenth century. In this article, we take a brief look at the history of the Dulwich set, examine its formation and possible sources. We will also take an in depth look at the portrait of Anne Boleyn and try to identify its role in relation to her iconography.

© The Dulwich Picture Gallery

Though, not necessarily known for their artistic quality, the Dulwich Picture set brings with it the unique documentation that allows us to see how and when this collection of portraits was bought. Originally purchased as a set of twenty-six portraits, all close in size, and, unified visually by the depiction of a blue skyline and a draped curtain in the background. The collection was bequeathed in its entirety to the Dulwich College by its founder Edward Alleyn in 1626.[1]

Born on 1st September 1566, Edward Alleyn was an English Actor who achieved ‘celebrity status’ in Elizabethan England. In 1592, he married Joan Woodward, daughter of Philip Henslowe, Groom of the Chamber. Alleyn and Henslowe would eventually go into business together and Alleyn would eventually become sole proprietor of several playhouses, bear pits and other rental properties across London. This made Alleyn a wealthy man, and on 25th October 1605, he purchased the manor of Dulwich, made up of 1500 acres of land and farms from Sir Francis Calton and began to build the College. Completed on 1st September 1616, God’s Gift College, as it was originally named, was granted a Royal Patent from King James I and, today, is more famously known as the Dulwich College.[2]

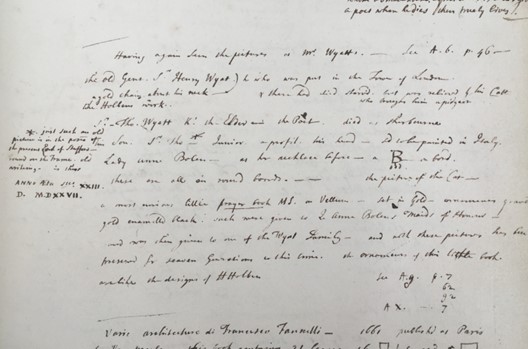

Though no inventory survives detailing the collection of Edward Alleyn, the college does have his original diary/account book in its collection. This account book details his expenditure and daily activities between the years of 1617 to 1622, and it offers the unique insight into the purchase and trade of paintings in seventeenth century England. It also shows us the exact sequence in which Alleyn purchased his portrait set of Kings and Queens of England and how much he paid for them.

In an entry written 29th September 1618, Alleyn records that he spent 200 pounds and bought the first set of paintings. This entry notes that Alleyn started his set by purchasing the portraits of James I, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Edward VI, Henry VIII and Henry V.[3] Just nine days later on 8th October, Alleyn returned to purchase another eight portraits of Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III and Henry VII, thus extending the sequence back to King Edward III.[4] A gap of almost two years is noted within the account book before Alleyn returned to purchase more paintings. On 25th September 1620, Alleyn purchases the portraits of Edward II, Edward I, Henry III, Richard I and Henry II. [5] He again returns one last time to complete his set on 30th September 1620, and purchases the portraits of Henry I, Stephan, William I, William II, the Black Prince, and Anne Boleyn. [6]

© Dulwich College, London

By the early seventeenth century, when Alleyn was purchasing his set of Kings and Queens, it had become relatively common for people of wealth to purchase paintings or engravings of political, religious, or influential figures. Artists workshops of the period were producing portrait sets of various qualities, quickly, with much focus on the authentic image and detail. These paintings were not only to decorate the home, but to also demonstrate loyalty to a specific cause. Today, only a small selection of portrait sets have survived, in some sort of entirety, however, many single paintings, which were once part of a set are now scattered among collections around the world. The publication of a variety of books containing written text and images of historical figures from many different sources began to be published in large quantities during the second half of the sixteenth century, and single-sheet engraved portraits were also becoming widely available for people of less income to collect and artists to copy.

Alleyn’s account book is unclear as to whether he purchased the set for his own home or to be displayed at the college, however, both places would have been a suitable dwelling for the set to achieve the impact it was designed for. It also needs to be remembered that around the time of purchasing the set, Alleyn was trying to obtain a Royal Patent for his college.

The surviving portraits of the Tudor Monarchs in the Dulwich set appear to be based on portraits completed by Holbein, Scrots and Antonis Mor, who as we know were all employed by the crown to produce an authentic likeness of the sitter. This demonstrates that the artist/artists who created the set were indeed looking and gaining access to authentic images of the more recent monarchs.

The surviving portraits of some of the earlier monarchs, from William the Conqueror up to Henry IV, show a close relationship in pose and detail to a set of engraved portraits by Renold Elstrack, published in Henry Holland’s ‘Baziliologia’ in 1618. The portrait of Henry V, purchased by Alleyn during his first shopping spree in the September of 1618, also appears to be based on the image printed in ‘Baziliologia’, which suggest that the workshop had obtained a copy of this book, or at least a single sheet containing the image of Henry V early in its publication.

© Public Domain

We do not know the specific reasons as to why Alleyn opted to wait two years to purchase further portraits of the earlier English Monarchs. It is highly unlikely that this was due to a lack of source material or that he had to wait for them to be painted. At 6s 8d each, the paintings were not an expensive purchase for Alleyn, and money does not appear to be an issue as his account book demonstrates that he made larger purchases between buying the initial portraits of the more recent monarchs and completing the set in 1620. It may just be possible that he simply made the decision to extend the set further back and opted to revisit the seller years later to achieve this.

Alleyn died on 25th November 1626, without any children, and left ‘hangings and pictures’ to the college in his will. The college later received a further bequest of two hundred and thirty-nine pictures from the actor William Cartwright, and it was then decided to put the entire collection on public exhibition. During the eighteenth century, the collection was displayed on the upper floor of the old college, however, by this point in time many of the portraits appear to have been in a state of disrepair. Art Historian Horace Walpole noted that the collection contained ‘a hundred mouldy portraits among apostle’s sibyls and kings of England’. The fact that the portraits received little attention in terms of conservation is possibly one of the reasons why the Dulwich portrait set is not complete today.[7]

Oil on Panel

22 3/8 x 16 5/8 inches

© The Dulwich Picture Gallery

In terms of the portrait of Anne Boleyn, it is currently one of three portraits depicting Anne that has remained in the same collection for a long period of time and has not been separated from its original set.

As we have seen with many other portraits in the study, the Queen is seen painted to just below the bust and is facing the viewers left. Anne is no longer placed in front of a plain background, and in accordance with the rest of the set, she is depicted in front of a curtain. Painted with the use of green pigment, the curtain is covering a window and seen under this is the inscription ‘ANN. BOLEYN.’ Anne wears her familiar French Hood on her head, constructed of black fabric with an upper billament showing thirty-nine pearls and a lower billament showing thirty-four pearls. Her gown is constructed with the same black fabric, cut square at the neck, and decorated with eighteen ouches and thirty-four pearls. Under this, she wears a shift of white fabric, also cut square at the neckline, however the familiar blackwork embroidery around the edge of this is missing. Around her neck, is a long strand of pearls with the now infamous ‘B’ Pendant hanging from them. Instead of the looped gold chain seen in the many other portraits of Anne, the artist has opted to depict another string of pearls. The portrait does appear to have been painted quickly, lacking some of the finer details, form and shadows seen in other copies.

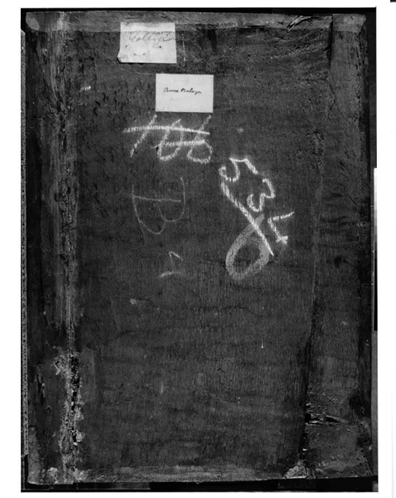

Constructed with the use of three uneven vertical panels of oak, cut to create one rectangular panel measuring 22 3/8 inches by 16 5/8 inches. The panel reverse contains two early labels detailing the sitters name and a small number of old inventory numbers has also been chalked onto the back.[8]

© The Dulwich Picture Gallery

The portrait has been painted with the use of oil paint; however, the painted surface is thin and much of the dark wood grain from the rough panel surface below is showing through and obstructing the original image. This can be seen on several portraits throughout the set, and would suggest that the images were painted quickly, with little time of effort put into preparing the panel surface for the paint application. As discussed above, the use of a pattern was used to create the image of Anne, and evidence of under-drawing in the face, hair and jewels is observed through the painted surface.

© Dulwich Picture Gallery

As we have seen from the entries written by Alleyn in his account book, the portrait of Anne Boleyn is the only image of a royal consort to be produced for the Dulwich set. It could be possible that this was simply an overhang from the reign of her daughter, Elizabeth, however the fact that this was painted almost fifteen years after her death is a mystery, and we will never truly know the reasons why Alleyn opted to include her.

Henry Holland did include an engraved image of Anne Boleyn in his 1618 book ‘Baziliologia’. Anne is again noted to be the only consort to be depicted in the book, and this may possibly be one of the reasons why she is depicted in the set. The Dulwich image is, interestingly, not based on Elstrack’s engraving of Anne, even though we know with some certainty that the artist/artists who created this image had used the Baziliologia engravings for other images produced in the set. The exact reason why the artist opted to use the B Pattern image of Anne, over the Baziliologia image is unknown. It may just be possible that the B Pattern had already gained acceptance as an authentic image of the Queen by this point in time and the artist simply opted to use this over the other image produced in Baziliologia.

Engraving

Renold Elstrack

© Public Domain

Unfortunately, the Baziliologia image of Anne created by Renold Elstrack has caused some debate over the course of time, as some art historians have argued that the engraving was possibly based on Holbein’s depiction of Queen Jane Seymour in the now lost Whitehall mural. The reason for this is that Anne is seen in the Elstrack engraving wearing similar jewellery and hood to that seen worn by Jane Seymour in the surviving copies of the Whitehall mural [9]

To me this theory has been accepted far too easily, and there are another two images of Anne Boleyn which in my opinion are closely related to the Elstrack engraving. Both depict Anne wearing an English Gable Hood, and both are identifiable by the use of the monogram AR. The first of these is known today as ‘The Moost Happi’ medal which is stored in the collection of the British Museum, London. Thought to have been struck during Anne’s lifetime for the expected birth of her second child in the autumn of 1534, it features an image of the Queen with her face seen in three- quarter view, like that seen in the Elstrack engraving. Unfortunately, the medal has sustained some damage to the nose at some point in its history, however, enough does remain untouched to establish some sort of face pattern. The sitter depicted has a long-oval face, high cheek bones, a strong chin, and perhaps, a prominent nose. She also wears a large cross attached to her necklace, which again is noted in the Elstrack engraving.

Anne Boleyn

1534

© British Museum, London

Unfortunately, little documentation has survived in terms of the household accounts of Anne Boleyn, and no complete Jewel inventory has, yet, surfaced to give us an in-depth view of the specific items held in her collection. Dr Nicola Tallis has recently published a fantastic book in which she takes a fresh look at what is known today as the ‘Queen’s Jewels’. In this, Tallis gives a unique insight into what is currently known about the personal jewellery belonging to Anne Boleyn and demonstrates how a collection of royal Jewels was passed down by Henry VIII to his wives. Tallis also notes that we do have at least three miniature portraits depicting Catherine of Aragon, Jane Seymour and Katheryn Parr wearing a similar cross to that seen in the Moost Happi medal and the Elstrack engraving, which does suggest that Anne Boleyn could have had access to one as part of the Queen’s Jewels.[10]

The second image is a panel portrait, formally in the collection of Nidd Hall, and now in a private collection. This image displays the Queen wearing and English Gable Hood, her face is three-quarter view, and once again she has that characteristic long-oval shaped face, high cheekbones, strong nose, and the firm chin as that seen in the Moost Happi medal and Elstrack’s engaging. Unfortunately, to date the Nidd Hall portrait has not undergone any scientific investigation to establish if the engraving could be based on this pattern or vice versa. [11]

Anne Boleyn

Sixteenth Century

Oil on Panel

© Private Collection

It could also be argued that the woman depicted in the Nidd Hall portrait has similar features to that seen in the B Pattern portrait, and this could be a more mature representation of the same individual. As with the many portraits associated with Anne Boleyn, until a chronological date pattern is established, we will never know for certain, and cannot rule out the fact that one could be an authentic image.

© Public Domain

What is most intriguing about the Dulwich portrait of Anne Boleyn is that it appears to be the closest in comparison to the Rawlinson, Radclyffe, Kentwell, and Hever Rose Portrait. As discussed in my previous articles, two distinctive patterns appear to have been used when creating images of Anne Boleyn. It is highly likely that the pattern used to create these four portraits was also used to create the Dulwich copy, however the artist opted to leave the hands and rose out of this version. The depiction of the Jewels and pearls are rendered with a much less refined technique than that seen in the Hever Rose, Radclyffe, and Rawlinson version, which suggests that these examples could possibly be earlier versions, however, this will not be known for sure until one of the copies has been dendrochronologically tested. I have heard from a reliable source that the Hever Rose portrait is due to have this scientific procedure completed, so all the Anne Boleyn community are currently waiting in anticipation of these results.

[1] Though Alleyn purchased a portrait of James I to be included as part of this set, the portrait of James which is in the collection today appears to be of a finer quality than that seen in portraits of the earlier monarchs. Some further research is required to establish if this was indeed the original portrait purchased by Alleyn or a later copy that has been adapted in style to correspond with the rest of the paintings.

[2] G. F. Warner. The Manuscripts and Muniments of Alleyn’s College of God’s Gift at Dulwich, 1881, p. V-IIV

[3] Dulwich College, London. MSS 9,32r, Diary and Account Book of Edward Alleyn, September 29th, 1617, to October 1st, 1622. 29th September 1618 ‘bought 6 pictures of K J(ames): Q E(lizabeth): Q M(ary): K E(dward VI): K H(enry) ye 8th and K H(enry) ye 5th’

[4] As above, ‘8 pictures off E(dward) ye 3: R(ichard) ye 2: H(enry) ye 4: H(enry) ye 6: E(dward) ye 4: E(dward) ye 5: R(ichard) ye 3: H(enry) ye 7.’

[5] As Above: ’25 September 1620 Bought 6 heds of E(ward) ye 2/ E(dward) ye 1/ H(enry) ye 3/ Jo(hn)/ Ri(chard) ye 1/ H(enry) ye 2/ Paid 6s 8d a peec’ .

[6] As Above. 30th September 1620 ‘paid for six heds of H(enry) ye 1st: Steven: W(illiam): Rufus: W(Illiam) conquer: black prince: an of bullen’

[7] The Athenaeum Magazine, Volume 1630, January 22nd, 1859. P. 112

[8] My sincere thanks to the Dulwich Picture Gallery for providing me with an image of the back of the panel and the condition report for the portrait of Anne Boleyn.

[9]Philip Mould Ltd, Lost Faces Identity and Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture, 6-18th March 2007, Page: 80

[10] Tallis, Nicola. All The Queen Jewels 14-45 – 1545 Power, majesty and Display, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2023 p.136-138

[11] The Nidd Hall portrait has recently undergone some cleaning and restoration work, however, no dendrochronology testing has, as yet taken place.