A Tale of Too Many Thomas’s

Anne Boleyn

Oil on Panel

10 inches in diameter

© Earl of Romney

The Romney Portrait is among a small group of paintings associated with the Iconography of Anne Boleyn which has rarely been seen or studied by any academic. Much has been written about NPG 668 and the Hever Rose Portrait, and in terms of a published image these two portraits tend to be the most popular when an illustration of Anne Boleyn is provided.

The Romney portrait has made a few public appearances. It was first exhibited in 1890, when it was featured among eight other portraits supposedly depicting Anne Boleyn in the New Gallery, ‘Royal House of Tudor Exhibition.’[1] The portrait appeared again in 1902, when it was displayed among portraits of other British Kings and Queens in the ‘Monarchs of Great Britain’ exhibition.[2]

According to tradition, the portrait has been in the collection of the descendants of the Wyatt family for over four hundred years and was claimed by members of the family to be an authentic likeness of the doomed queen. At first glance, everything appears to add up, and for the first time in this research we have a portrait with a long family tradition, inscription, and artists name, however, are things too good to be true?

Painted with the use of oil on a singular wooden panel, the portrait depicts the image of Anne Boleyn, which over the course of time has become ingrained in the mind of any viewer familiar to her story. The Queen is seen painted to just below the bust, facing the viewers left, and is placed in front of a plain dark background. On her head, she wears the French Hood constructed of black fabric with eighty-eight pearls visible. Her gown is constructed with the same black fabric, cut square at the neck, and decorated with twenty-four ouches and forty-three pearls set in gold. Under this, she wears a shift of white fabric, also cut square, with blackwork embroidery around the edge. Around her neck is a gold chain and a long strand of pearls with the now infamous ‘B’ Pendant hanging from them.

© Earl of Romney

Generally, the portrait is in relatively good condition, however, surface dirt and discoloured varnish has obstructed the image slightly, and the portrait would most definitely benefit from having some restoration work completed. Some large areas of paint loss around the edge of the panel are also noted which may possibly suggest that the painting has been cut down at some point in time. A small area of lifting/flaking paint can also be seen above the sitters left breast.

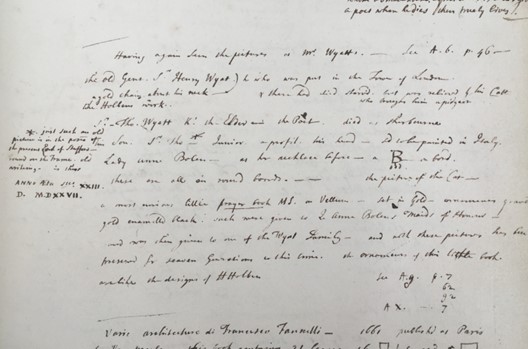

As seen in the image above, the portrait contains an inscription completed in a yellow pigment. This informs the viewer that the sitter is ‘ANNE BOLEYN. B. 1507. BEHEADED 1536’ and that the artist is ‘LURAS CORNELLI.’

The association with Lucas Cornelli or Cornelisz de Kock, as he is better known, is a tricky one. Cornelisz was a Dutch painter born in Leyden in 1493, he is today one of the more obscure artists from the Tudor Court. According to the seventeenth century biographer, Karel Van Mander, Cornelisz moved to England with his wife and seven or eight children and was eventually employed by King Henry VIII as the Kings Painter.[3] Unfortunately, no work that can be reliably identified as being by his hand, has yet, surfaced and the exact date in which he arrived in England is unknown. A set of nineteen portraits depicting the office of constable of Queenborough Castle in Kent, was once associated with him during the eighteenth century. Today, this set is now known to date to the1590’s, and the association with Cornelisz was made due to the wrong interpretation of the monogram ‘LCP’ on one of the portraits.[4]

Having undertaken a large amount of research into the iconography of Lady Jane Grey, I am personally very sceptical when it comes to portrait inscriptions. I am only one hundred percent convinced when the inscription has undergone rigorous investigation to identify if the inscription is authentic to the artists hand or not.

Oil on Panel

© Earl of Romney

Two further portrait’s depicting Thomas Wyatt the elder and his son Thomas Wyatt the younger, are also in the collection of the Earl of Romney. Both are of similar size and constructed with the use of a circular oak panel. Both also contain a similar inscription completed in yellow pigment as that seen in the Boleyn Portrait, and the portrait of Thomas Wyatt the elder is also associated with the artist Lucas Cornelli. Both these paintings contain an earlier inscription which indicates that all three portraits had inscriptions added to the outer area at a later period, rather than by the artist who created them.

Before we look at the provenance and documentation relating to the Romney portrait, we first need to take a brief look at the history of the Wyatt family and the properties associated with them. Allington Castle in Kent was the seat of the Wyatt family during the first half of the sixteenth century. It was purchased Sir Henry Wyatt as his principal residence in 1493, and the castle is less than twenty miles away from Anne Boleyn’s childhood home of Hever Castle. Much debate, myth and exaggeration has been had over the centuries as to the exact relationship between Thomas Wyatt the elder, son of Sir Henry Wyatt and Anne Boleyn. We do know for certain that both families knew of each other and most definitely mixed in the same circles. No record of a portrait of Anne Boleyn within the Wyatt family’s collection has yet surfaced, and no inventories listing the possessions at Allington Castle has survived. The castle remained within the Wyatt family until 1554, when it was confiscated by the Crown due to Thomas Wyatt the youngers involvement in the plot against Queen Mary I. His wife, Jane Hawte was left destitute after the execution of her husband, however, some of the Wyatt lands, not including Allington, were restored to her in 1555. In 1568, Allington Castle was granted by Queen Elizabeth I to John Astley, and it eventually passed through marriage into the hands of the Earls of Romney.

In 1570, Queen Elizabeth I restored further Wyatt lands, including Boxley Abbey and Wavering to Sir George Wyatt, son of Thomas and Jane Hawte. George became heir to all the Wyatt estates in that same year and he became fixated on the history associated with his family. He began a conscious effort to rehabilitate his family name and fortune by collecting family stories, papers, writing pamphlets, and he even wrote what would be the first biography on Anne Boleyn.[5]

On George Wyatt’s death in 1623, his collection of family memorabilia and the remaining Wyatt lands passed to his son Sir Francis Wyatt, then onto his son Edwin Wyatt in 1644.[6]

By 1725, we have our first piece of documented evidence concerning the Romney Portrait. This comes to us when the portrait was viewed and documented in the notebook of the eighteenth-century engraver and antiquary George Vertue. Vertue viewed the portrait on at least two separate occasions, and when seeing it he simply wrote a few lines noting that the portrait was:

‘In poss. Mr…. Wyatt in Charter House Yard. Picture of Q. Anne a Bolene. In a round (Frame) painted on Board.’

© Public Domain

Thomas Wyatt, son of Edwin Wyatt, also presented the portrait, along with a small prayer book to the society of Antiquaries in 1725. This viewing is again documented, and notes taken at the time indicates that Thomas Wyatt believed the portrait to be ‘original’. Also documented is the tradition that Anne gave the prayer book on the day of her execution to a member of the Wyatt family.

There does appear to be a tradition that Margaret Wyatt, sister of Thomas Wyatt the elder, attended Anne Boleyn on that fateful day in 1536. This appears to stem from an early manuscript regarding the life of Thomas Wyatt the elder, copied and published in the eighteenth century by Thomas Gray. Sadly, we know very little about the ladies who served Anne in her final hours. Contemporary descriptions of this event do not provide the detail of their names, and if discussed at all then they are simply referred as ‘her ladies’, ‘her women’, or ‘four young ladies’. No description of Anne giving out gifts when on the scaffold is also known to exist and Sir George Wyatt makes no mention of the prayer book or Margaret Wyatt supporting Anne on the scaffold in his biography on Anne Boleyn.

The direct Wyatt line died out in 1746, with the death of Thomas Wyatt, and it appears the small collection of family portraits and papers then passed to his aunt, Margareta, who was grandmother to the 1st Earl of Romney. The painting continued to be passed down the Romney family line and today, the portrait hangs on the walls at Gayton Hall, seat of the Earl of Romney.[7]

As this article demonstrates, the tradition associated with the Romney portrait of Anne Boleyn appears to be a rather complex one, and although once claimed to be an authentic likeness, this is not exactly known for sure. None of the Romney portraits have undergone any scientific investigation or dendrochronology testing to establish a date of creation, and the portrait of Anne Boleyn has not been seen in public for over one hundred and twenty years. The portrait itself probably dates to the end of the sixteenth century when descendants of the earlier notorious Wyatt’s were attempting to restore the family fortunes and lift the association of treason which had been applied to family name.

One clue does support this theory, stored in the Wyatt papers is a rather curious tale concerning Thomas Wyatt the elder, documented toward the end of the sixteenth century by his grandson Sir George Wyatt. According to Sir George, he was informed of the story from two sources: ‘One a gentleman, a follower of Sir Thomas and another a Kinsman of his name.’ Sir George then goes on to document the tale noting that when in Rome, Thomas ‘Wyatt stopped at an inn to change horses. On the wall of his chamber Thomas drew a ’Maze and in it a Minotaur with a triple crown on his head, both as it were falling’ and above this he placed the inscription ‘Laqueus contritus est et nos liberate sumus’’[8]

Oil on Panel

© Earl of Romney

Once attached to the back of the Romney portrait of Thomas Wyatt the elder, was a separate panel painting depicting the image supposedly drew by Thomas on the wall of the inn. As George documents this story at a later period and notes that he was informed of this by two other individuals, it is highly likely that George Wyatt had this painting created himself. This would also suggest the possibility that George had some of the Family portraits, as well as the portrait of Anne Boleyn, copied from available images as a way of promoting his family history.[9]

If indeed all three portraits date towards the end of the sixteenth century it would be tempting to suggest that since a portrait of all three sitters was recorded in the collection of John, 1st Baron Lumley in 1590, then it may just be possible that these portraits were used as the reference images for the Romney portraits. Unfortunately, until further examination is completed on the paintings, we will not know for certain the year in which all were create. However, since Sir George Wyatt went to much effort to rehabilitate the family name, it is highly likely that they all date to his lifetime.

[1] Exhibition of the royal house of Tudor : New Gallery (London, England) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive accessed 28/05/2023

[2] The monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland : Winter Exhibition, the New Gallery, 1901-2 : New Gallery (London, England) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive accessed 28.05.2023

[3] Het leven van Lucas Cornelisz. de Kock, Schilder van Leyden., Het schilder-boeck, Karel van Mander – dbnl, accessed January 2023

[4] Daunt Catherine, Portrait set in Tudor and Jacobean England, University of Sussex, 2015, Vol I, Page: 80 – 87

[5] Goeorge Wyatt’s book entitled ‘The Extracts from the Life of the Virtuous, Christian and Renowned Queen Anne Boleigne.’ Was published towards the end of the sixteenth century. 27 copies of the book were privately printed, and six copies are held in the British Library today.

[6] Edwin left his estate to his eldest son Francis, who died without children, leaving the estate to his brother, Richard, who also died without issue and was the last in this line of the Wyatt family. Richard left the land to a relative, Robert Marsham, Lord Romney (son of [Margaret] (Bosvile) Marsham.

[7] I am extremely grateful to the current Earl of Romney for providing me with the colour photographic images of this painting.

[8] Loades. David. The Papers of George Wyatt Esquire of Kent Son and Heir of Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger, 1968, Royal Historical Society, PP: 28 – 29

[9] The Wyatt Maze is no longer attached to the back of the Thomas Wyatt portrait as it was removed at an earlier period and now hangs directly next to the portrait of Thomas Wyatt the elder.